Meet Professor Carl Jones - the birdman

It’s a rare and special thing to be credited with saving a species from certain extinction and our Chief Scientist, Professor Carl Jones has been recognised for saving nine.

In 2016, Carl was awarded the prestigious Indianapolis Prize - the Nobel Prize for Conservation. His life’s work in Mauritius spanning more than 40 years is a source of optimism for countless conservationists around the world.Carl spoke to our Honorary Director, Dr Lee Durrell, about his inspiring career and working alongside his hero Gerald Durrell.

What was your childhood like?

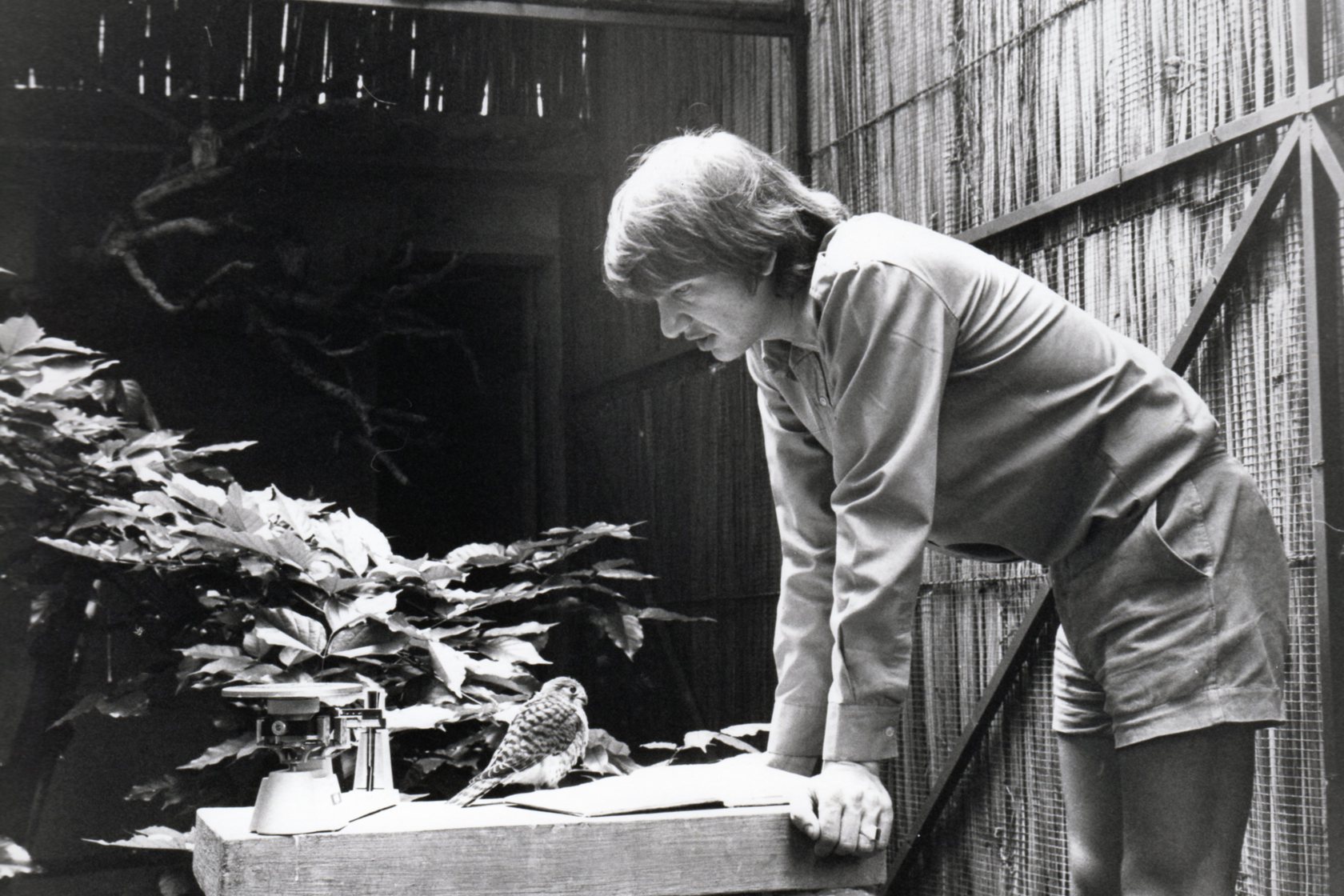

I was always animal obsessed; I loved nature, and spent my time poking around in hedges and along the riverbank. In primary school we had nature study lessons and a nature table with old nests, hatched eggshells, bones, snails and jam jars containing bugs and tadpoles. I still remember those lessons and I became a collector of natural objects, skulls, fossils and shells. I kept pet animals, starting with chickens, rabbits and pigeons, then progressed to keeping rescued wild animals. I reared fox cubs and badgers, frogs and pheasants, hawks and herons. For a while, I had so many animals that our back yard was full of cages and aviaries, and I had to play truant from school to look after them. These were formative times and I learnt how to keep a range of species, and bred slow-worms, kestrels, polecats and owls. It was as a schoolboy that I learnt the skills I used to help save some of the world’s rarest animals.

Describe your first meeting with Gerald Durrell.

I first met Gerald Durrell in 1980. I had been in Mauritius for a year and a half and Jersey Zoo already had some Mauritian animals. At the time, I was working for another organisation and had been corresponding with people at Durrell. On my first trip back to the UK, I came across to Jersey to discuss the work I had been doing and how we could work more closely. Gerry was warm, hospitable and very amusing; I was captivated by his command of language and his irreverent humour. He described situations and people with penetrating wit, picking up on nuances and subtleties that left me astounded by the lucidity of his perceptions.

At the time, the conservation situation in Mauritius was dire with many species about to disappear, and strong personalities and complex politics made the work difficult. Many felt that the approaches we were adopting to save the species were inappropriate. I was being overwhelmed by the conflict and I discussed this with Gerry. He listened

attentively, and after I had finished telling him of the challenges, he said there was no quick fix, and that he would have to sleep on the issues and tell me the following day what he thought. By the next morning he had sketched out a plan for how to move forward, with several solutions and the promise that he and the Trust would help with the work and how to negotiate the various complexities. I embraced Gerry’s ideas and together, with the rest of the Durrell team, you, John Hartley, Jeremy Mallinson, Simon Hicks and others, we developed our work in Mauritius and Rodrigues.

You often say that you are a disciple of Gerald Durrell. What was it about him and his work that inspired you during the nearly 20 years you knew him?

In common with many, I was inspired and enthralled by Gerry’s books. He described nature so beautifully and I loved the way he interacted with animals and entered their lives. He described a world that I could glimpse and wanted to inhabit. Gerry lived closely with his

animals, he took time to understand them and was very intuitive. To truly understand animals, you need that type of intimacy and then you can achieve a depth of understanding often impossible to reach with wild animals. He taught me that complex problems were solvable, but take time; you have to immerse yourself in the issues and then stand back to see them with clarity.

How important was it to you to have a mentor such as Gerry? Is having a mentor important for all young conservationists today?

Gerry was a huge influence. To this day I hear him whispering into my ear, sometimes telling me to stand back and give the situation some thought, or on other occasions to rely on my instincts and be bold. He encouraged us to use captive breeding and also to apply those skills to managing free-living populations. I have always been influenced by Gerry’s ideas, but also by his restless questioning and always striving to improve.

Conservation is rarely straight-forward. For most of the time I had to live with conflict and cope with naysayers. It was always good to know that I had Gerry’s support and I could bounce ideas off him. He would always be most encouraging, and after a long and constructive discussion about a particularly toxic situation, he reassured me, “don’t let the b*stards grind you down; I am always here to help”.

Having experienced mentors to guide you is the most efficient way for young conservationists to learn how to wend their way through the complexities of frontline conservation. In addition to Gerry, I also had the wisdom of others to call upon and I must acknowledge the help of Tom Cade, The Peregrine Fund, and Don Merton, Department of Conservation, New Zealand, who advised on a range of technical conservation issues.

One of the reasons Durrell has been so successful in conserving so many species is that we mentor the people and projects we work with over many years. This is however, a reciprocal process and we also learn a huge amount in return.

You have visited many countries, but have worked mostly in Mauritius. What is special about Mauritius?

I went to Mauritius for only one or possibly two years and it was made clear to me that I would be handing the project over to local biologists. My employers at the time felt that the situation was so desperate, they questioned the wisdom of investing in such rare species. I knew that my Mauritian colleagues did not have the resources or expertise to effectively manage the animals that meant so much to me. I soon realised that to have any chance of succeeding I would need to stay for several years. This was my greatest dream, and it was Durrell that allowed me to do it.

I was lucky that in Mauritius I was given a lot of freedom to tinker with the species and systems I was involved with. I enjoyed getting to know them, and the more I learnt, the more intense and amazing the relationship with them became. As soon as we started to be successful with one species, there was always another that needed help. As the species work gained momentum, it started to drive the restoration and rebuilding of habitats. The whole process engulfed my life and I could not think of anything else but the next step to restoring the damaged and lost systems. I love Mauritius, an island of dynamic colour and variety that tugs at my emotions. The country, people and wildlife will always be a huge part of my life.

Gerald Durrell had a specific way of undertaking his mission – saving species from extinction – which is still the mission of the Trust today. Does your approach now differ from Gerry’s and if so, how has it changed?

Gerald Durrell was a restless visionary who as always developing and growing his ideas. He instilled in us the difference we could make, and to always push the boundaries. Gerry is often portrayed as a champion of captive breeding; he was very much more than that. In the 1980s, he was thinking beyond the cages and wanted to know how to work effectively in the countries where the endangered species were found. He recognised that one of the answers to conservation was to empower people and develop local capacity by training their conservation biologists, and he saw species as the drivers for rebuilding their habitats. Gerry was always thinking of how to restore species within their habitats, and in his writings, he implicitly celebrates how important nature is for our well-being.

We have taken Gerry’s views, developed some, tweaked and modified others, and packaged them in our strategy, Rewild Our World. While we are a species- focused organisation, we are showing the world how long-term commitment to species can drive the restoration of whole ecosystems. Gerry would be deservedly proud of how we have all made his legacy grow and blossom.

How did you feel about winning the Nobel Prize of animal conservation – the Indianapolis Prize – in 2016?

It was my colleagues at Durrell that put me forward for the prize. When they were compiling the submission, I suggested that they were wasting their efforts since the previous winners had all worked on high profile species; elephants, cranes, pandas, lemurs and polar bears. I thought, what chance do I have working on pink pigeons and lesser night geckos? I was in Mauritius when I heard that I had won. I had a phone call late one evening and the news was a huge and very pleasant surprise. A wave of emotion engulfed me and my head filled with visions of the project highs and lows of the previous decades, but most of all I thought of all those colleagues, volunteers, interns and students from all over the world who had made our work possible.

Mike Crowther, the founder of the prize, explained that my submission had been overwhelmingly endorsed by the selection committee and that I had won, not only because of the species we have saved, but also for developing techniques and learning how to rebuild lost and damaged ecosystems. The committee was impressed that we were replacing the role of the extinct Mauritian giant tortoise by using Aldabra tortoises that are grazers and seed dispersers. Without these tortoises, it is likely that several plant species would become extinct.

You have worked for the Trust for more than 40 years and are still going strong. What motivates you now?

I have seen the Trust grow in influence and our projects have become more and more successful. I embrace our philosophies of working long-term on endangered species, working with local organisations, developing local capacity and how we are learning to reverse the damage that has been done to wildlife. I love our zoo and the work we do there, using it for training conservationists and helping people to connect with nature.

Much of the way Durrell undertakes its mission today is led by and influenced by you. Are you and the Trust on the right track? Give your favourite example.

Many of the approaches we have developed in Mauritius are being applied to some of Durrell’s other projects. What is really encouraging is that these projects are being developed further, demonstrating that these ideas work, and have great potency whether applied to mountain chicken frogs, pygmy hogs or red-billed choughs. Much of this is in the fertile area between captivity and the wild, working with semi-wild or free-living populations. We are taking the ideas of captive breeding, of how to improve survival and breeding rates by careful care, and applying them to free-living populations. Durrell is taking its captive breeding skills into the field, we are world leaders and have probably saved more species from extinction than any other organisation and this is driving the rebuilding of islands, marshlands, forests and grasslands.

I love all of our projects; the work on mountain chicken frogs in Montserrat where we are looking to manage the disease they suffer from under field conditions, is impressive. Of course, I am extraordinarily fond of the red-billed chough restoration in Jersey that was based upon work we did in Mauritius on the echo parakeet. Let’s look forward and apply the Durrell approach to looking after a population of the rapidly declining giant jumping rat in Madagascar.

What are your hopes for the future of biodiversity conservation, which is faced with enormous challenges globally, such as habitat degradation and climate change? Do you think Durrell’s approach will meet the challenges or must it evolve? If so, how?

Modern conservation philosophies have hamstrung our thinking. The idea that we can save wildlife by setting up protected areas and restore systems to their once pristine state is limiting. Of course, where we can protect and restore, we must. However, in a rapidly changing and dynamic world, protectionist approaches are not enough; if we had embraced these, most of the species we work with would have died out. In damaged and modified systems, you have to help the failing populations, and here, a medical analogy is fitting. When critically endangered, species may need intensive care; we nurture the failing populations with our skills; by mitigating the limiting factors and improving survival and breeding, that is by giving life sustaining care.

There has been a debate raging for decades in conservation biology, do we invest in saving species or do we conserve ecosystems? The reality is, as we can show, saving species drives the restoration of habitats and ecosystems. Durrell’s interest in the pygmy hog in the late 1960s and 1970s led to captive breeding and reintroduction, and is growing into work restoring the grasslands in Assam.

We are showing the way forward in saving species, rebuilding systems, and training the next generation of conservationists.

In true Durrell fashion, we need to be restlessly striving to improve. We are developing the tools for saving species and building ecosystems that are efficient sequesters of carbon. Durrell has the answers; we are making steps towards solving major problems.

You have told us what your childhood was like. What will your old age be like?

I am still doing many of the things I was when in my twenties, although more of my time is spent advising and mentoring other projects, giving lectures, and writing. I enjoy all of these hugely. I am now based in mid-Wales with my family where we have a small-holding, although I still travel a lot and usually visit Mauritius twice a year for a month or more on each trip. I still keep animals, and having school-aged children gives me the excuse to keep the pets I had as a child – rabbits, chickens and guinea-pigs, and we also have macaws, owls, hawks and cockatoos. My greatest pride is a breeding pair of Andean condors.

I would like to spend the coming years working with the next generation of conservation biologists, developing the scholarship fund, mentoring and helping where I can, and developing some new projects in Jersey and the UK.